Architectural Smells

Arcan bases the estimate of Technical Debt on the detection of Architectural Smells, software design decisions that negatively impact the software quality. Smells violates design principles.

At the moment, Arcan detects seven types of Architectural Smells:

- Cyclic Dependency

- God Component

- Hub-Like Dependency

- Unstable Dependency

- Cyclic Hierarchy

- Deep Hierarchy

- Wide Hierarchy

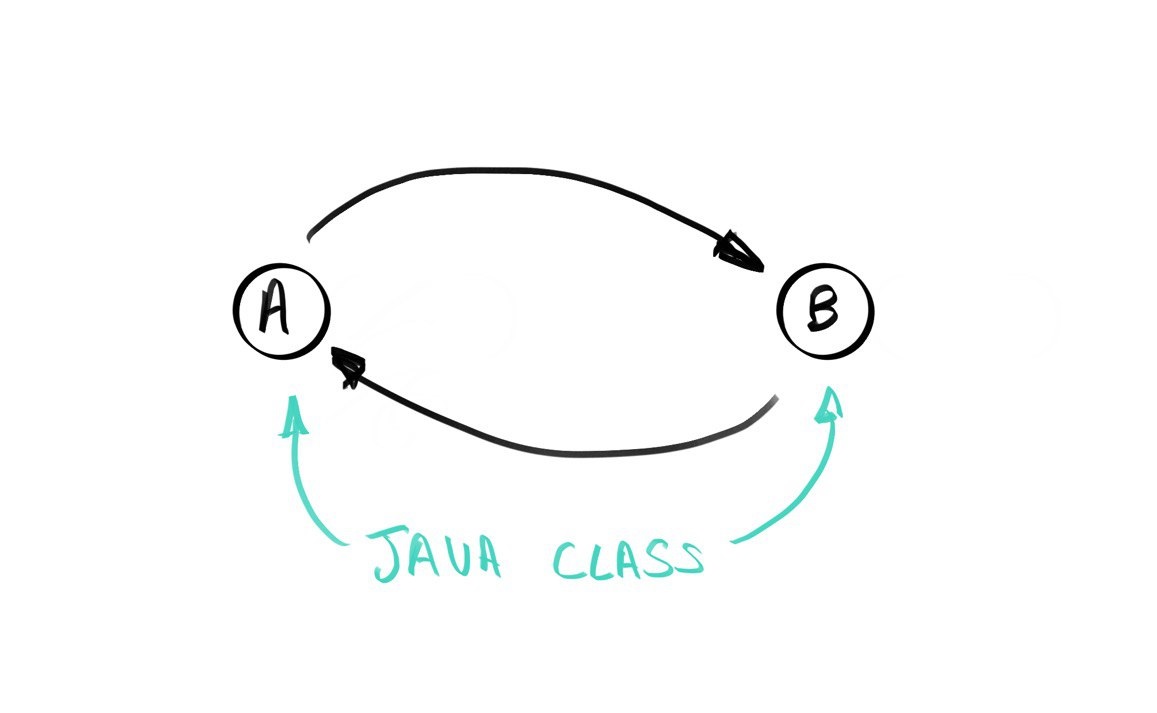

Cyclic Dependency

When two or more architectural components are involved in a chain of relationships.

Drawbacks

The architectural components involved in a Cyclic Dependency are:

- hard to release

- hard to maintain

- hard to reuse in isolation

The smell violates the Acyclic Dependencies Principle defined by R. C. Martin.

Detection strategy

The detection of Cyclic Dependency (CD) in Arcan is done using the dependency graph of the system that we are analysing, i.e., the graph representation of the system's architectural components and dependencies.

CD is detected on both units and containers (e.g., classes and packages in Java). A cycle is detected whenever two or more architectural components depend upon each other in a cycle. Arcan detects CD on different types of components and uses well-known cycle detection algorithm to identify components that belong to the same cycles. The algorithms supported by Arcan are:

- Sedgewick-Wayne algorithm, a simple DFS-based algorithm to detect cycles. More information here. This is the default implementation used by Arcan.

- Tarjan's strongly connected components (SCC) algorithm. You can find more here

- Laval-Falleri's shortest cycles algorithm. You can find more here. This is the default implementation used by Arcan for Layered Cyclic Dependencies.

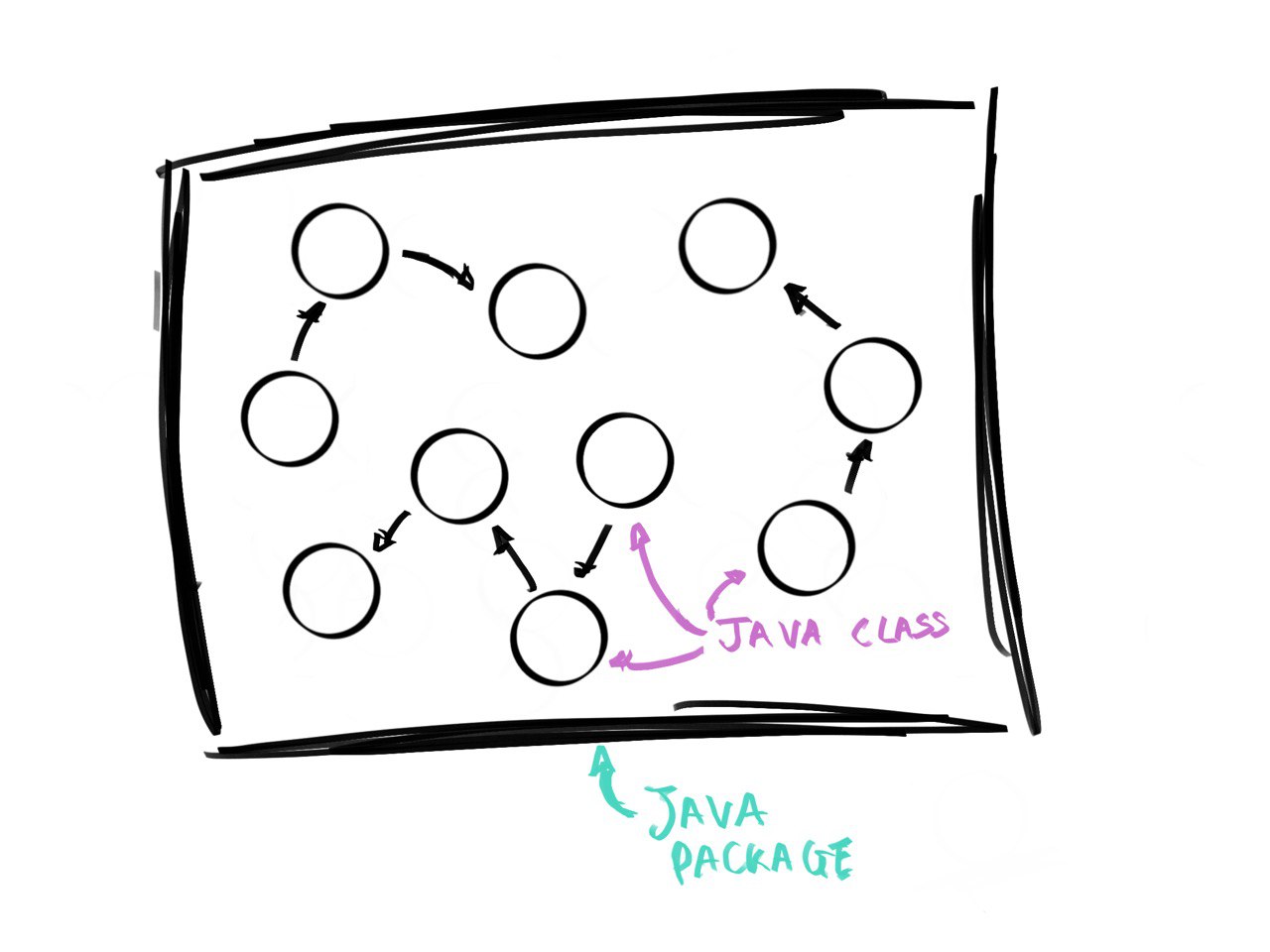

God Component

This smell occurs when an architectural component is excessively large in terms of LOC (Lines Of Code).

Drawbacks

The architectural component affected by God Component:

- centralizes logic

- has low cohesion within

- has increasing complexity

The smell violates the Modularity Principle defined by R. C. Martin.

Detection strategy

The detection of the God component (GC) smell is done using the size, in terms of number of lines of code, of the system analysed.

GC is detected at the container-level (e.g., packages in Java). The smell detection is based on Lippert and Rook's definition of GC, which is based on the total number of lines of code contained in the package.

While Lippert and Rook suggest to use a fixed threshold of 27.000 lines of code to detect the smell, our approach is more sophisticated and data-driven.

We calculate the detection threshold dynamically. The threshold is calculated as LinesOfCode = Max(LinesOfCode_System, LinesOfCode_Benchmark) where each individual LinesOfCode_* is calculated using frequency analysis of the metric LinesOfCode computed on the system and the benchmark separately. The metric is calculated as the total number of lines of code of all the elemnts belonging to a specific component.

The specific approach used to calculate the threshold is detailed here.

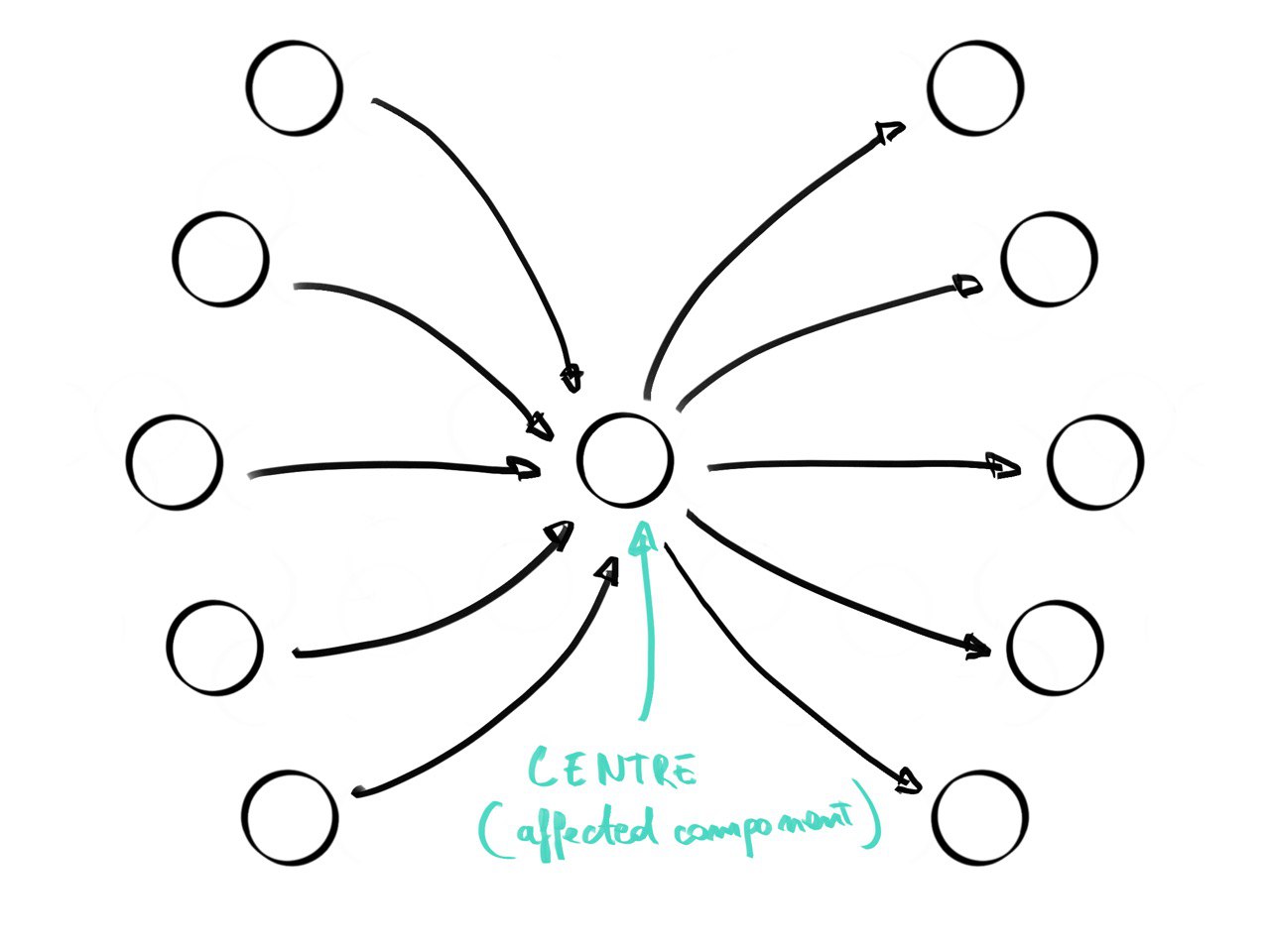

Hub-Like Dependency

When an architectural component has (outgoing and ingoing) dependencies with a large number of other components.

Drawbacks

The component affected by the smell:

- centralizes logic

- is a unique point of failure

- favors change ripple effects

The smell violates the Modularity Principle defined by R. C. Martin.

Detection strategy

The detection of Hublike Dependency (HL) in Arcan is done starting from the dependency graph of the system under analysis.

HL, or simply "hub", is detected on both units and containers (e.g., classes and packages in Java). A hub is detected whenever a component in the system has "too many" incoming and outgoing dependencies (FanIn and FanOut, respectively). The "too many" is calculated using a dynamic threshold that is based on both a benchmark of 100+ systems (from the Qualitas Corpus) and the system under analysis. This allows us to not pick the the threshold arbitrarily, but instead use a data-driven approach.

In particular, the threshold is calculated as Threshold = Max(Threshold_System, Threshold_Benchmark) where each individual Threshold_* is calculated using frequency analysis of the metric TotalDeps computed on the system and the benchmark separately, where TotalDeps(x) = FanIn(x) + FanOut(x) for all components x.

The specific approach used to calculate the threshold is detailed here.

Unstable Dependency

Describes an architectural component that depends on other components that are less stable than itself. Instability (proneness to change) is measured using R. C. Martin’s formula.

Drawbacks

The component affected by the smell can:

- favors change ripple effects

- be subjected to frequent changes

The smell violates the Stable Dependency Principle defined by R. C. Martin.

Detection strategy

The detection of Unstable dependency (UD) is done using the dependency graph of the system under analysis.

UD is detected at the container-level (e.g., packages in Java) only, whenever a container depends on other containers that are less stable than itself. By Instability we mean R.C. Martin's Instability metric, whose definition can be found here. Instability calculates how easy it is for a container to change because of other containers (e.g. packages) in the system have changed. Namely, it is a measure of the risk of ripple change effects.

The detection rule is the following: Intability(x) > Instability(y) + delta for all containers y such that x depends upon, and x is the container (e.g., package) that we are checking for the presence of UD.

Cyclic Hierarchy

This smell arises when a supertype in a hierarchy depends on any of its subtypes.

Drawbacks

The main problem with the supertype having knowledge of one of its subtypes is that changes to subtypes can potentially affect the supertype.

Modifications to or removal of subtypes may potentially affect supertypes, which may in turn affect other subtypes in the hierarchy. Such ripple effects often manifest as runtime problems. These factors affect the changeability, extensibility, and reliability of the hierarchy.

In this presence of this smell, a supertype cannot be used independent of its subtype. This impacts the reusability of the supertypes.

The supertype cannot be tested independently of the subtype(s) it depends on, impacting its testability.

Deep Hierarchy

This smell arises when an inheritance hierarchy is excessively deep.

A hierarchy that is excessively deep significantly increases the difficulty in predicting the behavior of code in a leaf type since the type inherits a relatively large number of methods from its supertypes.

Drawbacks

As the hierarchy becomes deep, it significantly increases the difficultly in predicting the behavior of a leaf class since the class inherits a large number of methods. Further, it makes the design more complex. These factors impact the understandability of the design.

When a hierarchy is deep, it is difficult to figure out what types to modify within the hierarchy to implement change or enhancement requests. Further, when any modification is done in types closer to the root of the hierarchy, it is difficult to determine the ripple effects of the change on its descendant types since the hierarchy is deep. This impacts the changeability and extensibility of the design.

It may require more effort to test unnecessary intermediate types in a hierarchy that is deep (when compared to testing a hierarchy without those intermediate types). Further, because some methods in the hierarchy that is deep could have been overridden multiple times, it is harder to test the overridden methods in the hierarchy. These factors impact the testability of the hierarchy.

A method from a supertype close to the root of the hierarchy may be overridden many times in the hierarchy. Hence, in the leaf types, the semantics of the inherited method may not be clear. In a similar vein, a field defined in a supertype may be hidden (or shadowed) in one of the methods in the subtypes. Confusion that ensues from overriding or hiding often leads to runtime problems, impacting the reliability of the design.

Wide Hierarchy

This smell arises when an inheritance hierarchy is too wide indicating that intermediate types may be missing.

Drawbacks

When intermediate abstractions are missing, the sibling classes are not at the same level of abstraction and the programmer has to do a “logical leap” to move from higher levels of abstraction to much lower levels of abstraction. This impacts the understandability of the hierarchy.

When hierarchies lack intermediate abstractions, the clients are forced to depend directly on lower-level abstractions. Since lower-level abstractions are more susceptible to change, there is a higher possibility that the client code may also get impacted. Hence, in the presence of this smell, changeability of the hierarchy is impacted.

One of the advantages of a properly designed hierarchy is that the types serve as “hook points” or “placeholders” for future extensions. Since some intermediate types are missing in the hierarchy, it affects the extensibility of the hierarchy.

An advantage of a properly designed hierarchy is that the types serve as interfaces to client code. Since some intermediate abstractions are missing in a Wide Hierarchy, it reduces the reusability of the hierarchy.